Written by Tim Anderson, Associate Professor of Communication and Theatre Arts at Old Dominion University.

In the history of African American media, none has been more proliferate and influential than music. As Arthur Knight points out in his book, Disintegrating the Musical: Black Performance and American Musical Film, for W.E.B. Du Bois music was the most important “gifts of black folk.” Knight understands the term gift as a complex one that bears meanings of communication, ethical commitments and essential (Knight 2002, p. 5). However, as a gift the issue of control quickly comes to the forefront. For Knight, mass mediation such as print notation, sound recording, broadcasting, and film throws the black gift into crisis. … Under mass mediation, music does not simply float as sound carried through air away from its going, producing, social bodies; rather it is captured and carried away, to be re-presented under circumstances whose relation to he sounds ‘original’ affiliated sight and story may be very different (Knight 2002, p. 6). At worst, Knight points out, that “the potential moral circuit of the gift that Du Bois desired becomes, at best the abstraction of selling and, at worst, ‘property’ theft” (ibid.).

The ability to rectify this problem has typically eluded most ordinary African Americans who do not have access to the significant amounts of capita necessary to manufacture and distribute this gift. Throughout the twentieth century this has meant reliance on labels and publishers, most of whom assumed control of theses gifts. Indeed, this has been a problem for even the most important popular musicians well into the 21st century. For example, the front page of the March 2nd, 2002 edition of Billboard declared “Black Artists Struggle to Regain Ownership of Master Recordings”. Noting that for numerous black performers have long had problems with royalties, among those few held up as examples to be admired were Ray Charles, Sam Cooke, Quincy Jones, Lamont Dozier, Al Jarreau and Curtis Mayfield. Indeed, for most big-name musicians, the ability to own one’s master recordings is a significant and rare achievement that allows artists and estates to shop their wares around for licensing deals once their initial contracts have expired. Artists such as Cooke, Dozier, Jones, Jarreau and Charles were able to secure their masters from their labels through savvy contractual negotiations where their clout and financial security allowed them such freedom. However, unlike these artists, the late Curtis Mayfield understood the importance of this business goal. Mayfield and his partner, Eddie Thomas, founded a 1968 label with the explicit aim of securing his future masters. With the same name of his already-existing music publishing company, Curtom records set forth on a rare business mission. As the late-Mayfield manager Marv Heiman noted, “In this days it was unheard-of for a performer/songwriter to own his own publishing, let alone his masters. [However], when Curtis started Custom, we both felt that whomever we did a distribution deal with, we wanted those masters to come back to us after a brief sell-off period. It was a material point of our deal” (Mitchell 2002, p.89).

Most famously known for his work with The Impressions and his 1970s solo work, Curtis Mayfield would be forever known if he had only written for his pop-gospel classic, “People Get Ready”. However, his work as a songwriter, musician and producer far exceeded the song. Throughout the 1970s Mayfield’s work would be a major piece of the 1970s post-civil rights, soul music movement. Indeed, Mayfield’s prodigious abilities became apparent in his teens as Mayfield joined with Jerry Butler in the Westside Chicago housing projects of Cabrini-Green to form a number of doo-wop groups that would become The Impressions. Establishing his original songwriting credentials at a very early age Mayfield was able to co-establish Curtom publishing with The Impressions’ manager, Eddie Thomas, by 22. By 1965, a twenty-three year old Mayfield was able to claim co-ownership of the Curtom publishing company with over a 100 songs in its catalog including hits by Major Lance, Jerry Butler and his own group, The Impressions. In 1965 Mayfield would form his own publisher, Chi-Sound Publishing, that he would own outright. As noted Chicago Soul historian Robert Pruter points out, “Curtom at one point in time was handling six different publishing companies” (Pruter 1991, p. 305). By 1968 Mayfield decided to form the Curtom record label, a business that would be able claim the entirety of Curtis Mayfield’s 1970s output, including the multimillion selling soundtrack to Superfly.

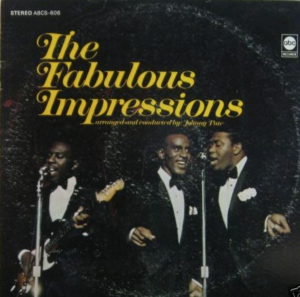

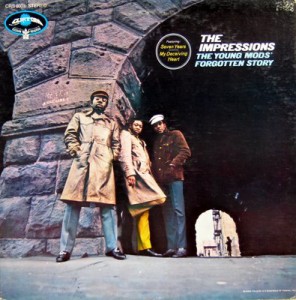

Still, retaining the rights to both the masters and publishing may be both Curtom’s greatest and least-acknowledged success. As Craig Wenner notes, Mayfield had already failed with two record labels — Windy C and Mayfield — before he and Thomas realized Curtom. The distribution problems that plagues the two previous attempts provided Mayfield and his partners “invaluable experience with the business and production aspects of the music industry” (Werner 2004, p. 143). For Werner the label provided an emblem of “black power” for more than a decade (ibid.). Werner argues that the power of this change is easily digested by simply doing a before and after comparison of the albums covers of The Impressions’ last two ABC-Paramount releases – We’re a Winner (1968) and The Fabulous Impressions (1967)- with their first two Curtom releases – This is My Country (1968) and The Young Mods’ Forgotten Story (1969) (pp. 143-144). While the ABC-Paramount releases provide examples of Mayfield’s band dressed in tuxedos and suits, the Curtom releases have The Impressions in much more modern threads.

Decked in turtlenecks outside a dilapidated tenement, the title of The Impressions’ first Curtom release is both a claim and acknowledgment. In the case of the latter, The Impressions statement that their country was falling apart was a recognition of their West Chicago neighborhood of Cabrini-Green, whose public housing units had by the early 1960s been all but abandoned by middle-class whites who simply did not want to integrate. As white flight deracinated the tax base, the neighborhood crumbled under the weight of thousands of dreams deferred. The second album expressed Mayfield’s stories expressed as forgotten hopes. Indeed, Mayfield never forgot the imperative of a better, more soulful world, signing the back cover of the record’s sleeve with the declaration that “People must prove to the people a better day is comin for you and me”.

Of course, these new Impressions records and Mayfield’s later output on Curtom sported potent political observations in lyrics wrapped in the sweetness of Mayfield’s sounds and arrangements. And as the label’s success grew, the label would both eventually purchase and move on up to studio on Chicago’s Near North side Mayfield sold his masters and publishing to Warner Brothers in 1980. However, his replacement in The Impressions, Leroy Hutson, had reached agreements with Mayfield in the 1970s that he could retain the masters to his solo work on the Curtom catalog, a gift that Hutson continues to hold onto to this day. Indeed, it’s an example that all musicians would do well to heed now and into the future if they hope to hold onto their soul.

Bibliography

Knight, A. (2002). Disintegrating the Musica: Black Performance and the American Musical Film. Duhram, NC, Duke University Press.

Mitchell, G. (2002). Black Artists Struggle To Regain Ownership Of Master Recordings. Billboard: 1, 89-90.

Pruter, R. (1991). Chicago Soul. Chicago, University of Illinois Press.

Werner, C. (2004). Higher Ground: Stevie Wonder, Aretha Franklin, Curtis Mayfield, and the Rise and Fall of American Soul. New York, New York, Crown.